Worth the Read

By Gordon Walmsley

Reviews of K by Katarina Frostenson, Den Nordiske MeToo Revolution 2018-og dens omkostninger by Marianne Stidsen, and The Cenci by Percy Bysshe Shelley

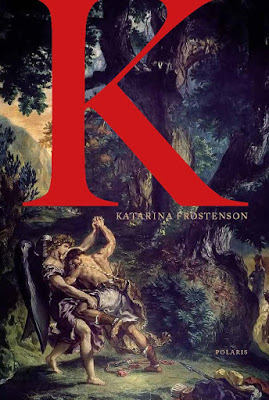

K, by Katarina Frostenson

Polaris. Stockholm 2019

in Swedish

Katarina Frostenson, the Swedish poet, has written a lovely book. Much to the dismay of those who would crucify her. For the book requires a reader whose perceptive apparatus is made of a malleable substance, free of atrophy.

For some reason that is difficult, but not impossible, to understand, there are those in Mrs. Frostenson's country, who want the blood of artists, theater people and poets. One remembers Ingmar Bergman being dragged out of a rehearsal in Stockholm by the Swedish police, for tax evasion, handcuffed before the eyes of his actors and actresses. (Wouldn't a letter have sufficed, one thinks.)

Early sensing the potential of unsubstantiated defamation, anonymous witnesses appeared in the sensation-hungry press to suggest that someone had been whispering secrets to Katarina Frostenson's husband, of who had won the Nobel Prize in Literature in a particular year. No crime, as we know, even were the accusation true. Someone or some ones had told these anonymous people who the winner would be, before the winner was officially announced.

Suddenly, an accusing finger is pointed towards the wife. For SHE was a member of the Swedish Academy, whose task it is to award the Nobel Prize in Literature. She must have told him! The wife! Of course, there was no proof. But proof is not necessary in a world where defamation is elevated to the status of justice.

Through all of this, Katarina Frostenson was silent and did not participate in the hysteria. Why engage in a game in which one senses the cards are clearly stacked?

Without recounting all the details, let us just say that Mrs. Frostenson's husband, Jean-Claude, was roundly beaten and dragged through the Swedish mud by even more anonymers and the rapacious Swedish press who positively hate "elitist" poets (Why can't she write poetry we can understand! one hears their desperate cries to heaven) and "elitist" institutions such as the Swedish Academy.

The sad tale reaches is wild denouement with Mr. Arnault being accused and convicted (two and a half years) of Swedish rape (non violent, non consensual), an accusation he has denied. One woman's word against a man's, with no witnesses present. Reasonable doubt? Apparently such standards did not apply.

Throughout all this, a pervasive silence from Katarina Frostenson.

Until the publication of this book.

I took the train to Sweden to get the volume, whose title is K. Three quarters of an hour from Copenhagen to Malmö (pronounced mal-merr). There were two copies left in the only bookstore in town that still had K.

Of course, the events of Katarina Frostenson's nightmare form the background of this work. The wind blows constant, from a certain direction and she sets her sails accordingly. And, yes, there is an element of defense. But the book is more an interior monologue over a certain tapestry, the tapestry being the events in the writer's life. Poems emerge, both by herself and others, remembrances appear, her flight from Sweden with her husband, embraced by the largesse that is France, walks and meditations, thoughts about poetry and life and injustice. And permeating the book, a spirit of absolute honesty. A marvelous creation, varied and ineluctable.

Anger sometimes makes its presence known, but it is the holy indignation of one who is the victim of calumny. The writer, besieged by a fulminating Swedish press, blood-hounding their way into the poet's life, seeks refuge in France, the land where Oscar Wilde fled British puritanical intolerance to live out his final years.

It is amusing to read some of the Swedish newspaper reviews of Katarina Frostenson's superb book. They reek of frustration. They are so angry. It is the frustration of someone who is furious because he or she can't understand a poem she has just read. This stupid "elitist" writer had dared to write something I do not understand. How dare she. She won't get away with this.

K is a beautiful effort, quiet in its tone, honest as honest can be.

I remember a poem by Goethe. It is nearly untranslatable so I will leave it in German:

Höre den Rat den die Leier tönt;

Doch er nutzet nur wenn du fähig bist.

Das glücklichste Wort es wird verhöhnt

Wenn der Hörer ein Schiefohr ist.

Schiefohr, an invention of Goethe it seems, for those whose ears can not fully hear.

Den Nordiske MeToo Revolution 2018-og dens omkostninger (The Nordic MeToo Revolution, 2018, and the Price it Pays. eds.) by Marianne Stidsen. U Press.

This book is a competent attempt to illuminate three examples of how calumny, group pressure, the howling mob, can infiltrate a society so that important cultural institutions (in this case, Copenhagen University, The Swedish Academy and the (Danish) Writer's School) are harmed by false tongues. It is not about the MeToo movement per se but more what has followed in the wake of it in Denmark and Sweden.

Marianne Stidsen is one of the more lucid heads on the Danish and Swedish cultural scene. She describes the situations she analyses with resolve and a good degree of courage.

We are talking here about a world where rumors are given the status of a proper juridical process and where one woman's voice is enough to ruin the reputation of the person under attack. Loosely founded rumor-mongering may not be new to this world, but what is new is the means of spreading, intensifying and encouraging various forms of defamation by means of the internet and "social media."

Of course, the use of power and position to obtain sexual favors is a terrible thing. But that is not what the book is about. What it is about is the use of duplicity in the furtherance of self-seeking goals. Stidsen gives well documented examples of how a small group, or even one person, can use defamation as a way of bringing about its (or her) own aspirations to power. Defamation is a technique that, by its nature, never actually converses with the person whose destruction the attacker seeks. It is the spirit of the diatribe as opposed to the spirit of dialogue.

The book is a good supplement to Katerina Frostenson's K.

Stidsen sees great danger in a growing tendency to replace sound judgement with hateful vengeance, easily transmitted online. She fears that unreasoned behavior of the kind she describes can encourage a new form of totalitarianism: McCarthyism, for those who remember it, the pressure of the group, seems disturbingly near. One hears in the distance the cries of the mob seeking blood. One remembers the French and Russian revolutions' insistence of a uniform way of compelled thinking.

The Cenci (1819) by Percy Bysshe Shelley

On the eleventh of September, 1599, Beatrice Cenci felt the blade that would send her over the threshold of the sense world. Together with her step mother and two others, she had bludgeoned to death her dissolute father, Count Franceso Cenci, a deed that did not sit well with the current Pope, the Canon Law expert, Clement VIII. True, Cenci was what we would today in our liberal use of vilification describe as a "monster". He was not a nice man. Indeed, he had a history of abusing both his wife and her sons and he had raped his beautiful daughter many times. This was more or less common knowledge in Rome of the day. But despite the abominations this horrible man brought about, the Eternal City, at the end of the sixteenth century was run by a few families and the Pope, families that were no doubt wont to cover each others backs. If they weren't intent on plunging a knife into them.

Many people were glad to see Cenci dispatched by an avenging daughter. She had the sympathy of Rome. Guido Reni painted her while she was in prison. This beautiful portrait shows a sensitive yet resolute soul. Her combination of "gentleness" and fury makes her character intriguing. We understand and sympathize with her. But the Pope, the ultimate arbiter of her case, feared a wave of parricides and felt compelled to make an example of Beatrice. And thus, with a small ax, she was duly beheaded that day in September on the Ponte Sant'Angelo in Rome.

The story still resonated two hundred years later when Percy Bysshe Shelley encountered it. He sensed the stuff of drama. I confess to being a lover of Shelley's poetic work, but also one who had never read The Cenci. It has hung there, ripe for the plucking, until now, a mystifying presence. Initiating a love for Italian domestic drama that would culminate in Browning, Landor and Ezra Pound, Shelley begins his preface:

"A Manuscript was communicated to me during my travels in Italy, which was copied from the archives of the Cenci Palace at Rome, and contains a detailed account of the horrors which ended in the extinction of one of the noblest and richest families of that city during the Pontificate of Clement VIII, in the year 1599." He was hooked. "The story is" he goes on to say, "that an old man having spent his life in debauchery and wickedness conceived at length an implacable hatred towards his children; which showed itself towards one daughter under the form of an incestuous passion, aggravated by every circumstance of cruelty and violence..."

The play doesn't follow the historical "facts" to the letter; there is no bludgeoning, but Shelley makes Beatrice into a determined and inventive murderess. It is not she who wields the final sword, or hammer, but she is clearly the moving agent of the crime. When her two hirelings return with the deed unconsummated, she sends them back, enraged. Shelley whets our appetite for final justice by revealing to us a horrible person. He does this in verse, iambic pentameter. And yes, it is hard not to compare The Cenci to Shakespeare, much as it is impossible not to compare all verse drama in English to the him, as T.S. Eliot despairingly remarked, when attempting his own verse play.

"Camillo [a cardinal]:

That matter of the murder is hushed up

If you consent to yield his Holiness

Your fief that lies beyond the Pincian gate..."

Thus begins the play. Cenci is buying his way out of yet another crime. And the Pope is profiting from yet another source of income. So get on with your murders dear Cenci... Cenci boasts of his ways and throughout the play shows no signs of remorse. He revels in what he is:

"As to my character for what men call crime

Seeing I please my senses as I list,

And vindicate that right with force or guile..."

Not a nice person. Cenci even throws a banquet to celebrate the death of his sons.

"My disobedient and rebellious sons

Are dead!" he enthuses.

And on and on until we are fully on the side of Beatrice.

Is he worse than the male "predators" of our day? Much worse. There is no doubt of his guilt, he freely admits what he does and has done. And he boasts that he is permitted his crimes because of his power.

The Cenci was first performed in a private performance sponsored by the Shelley Society in 1886. In the audience were Robert Browning, Oscar Wilde and George Bernard Shaw.

The play had its first public performance in London in 1922, a hundred years after Shelley's death. The themes of parricide and incest were thought unsuitable for theatre before then. Since that year, Shelley's work has been performed a number of times in many countries, more recently in Tehran, Iran. In Persian.

If you are unable to see it, you can at least read it.